By 2030 the number of public Level 2 chargers needs to reach more than two million and the number of DCFC stalls should hit 172,000. “That’s a lot,” said Marnie Abramson, principal and founder at Lightility, as she discussed the challenges involved with Jennifer Leonard, senior associate and practice leader at KCI Technologies at the recent EV Charging Infrastructure Summit virtual conference.

Abramson highlighted a three-pronged approach involving on-site planning, engineering and design, followed by construction and installation must be underpinned by local expertise on zoning requirements and utility providers. “Really reach out and make sure you are working with a local subject matter expert,” advised Leonard. While procurement costs are largely quantifiable, Abramson said so-called ‘soft costs’ such as liaising with utilities and providers, future-proofing and permitting processes can vary enough to sink a project.

Contrary to expectations, suggested Abramson, a DC fast charger might not be the best option. Customer requirements vary and you need to know what they are. The biggest cost drivers are power rating of the charges, existing onsite grid power capacity (some utilities don’t know their capacity) and charger location within the site. Utility providers may share costs, seeing a revenue source with ROI. Others will submit significant bills for engineering and upgrade costs, so partnership working is key.

Abramson urged providers to get to grips with both in-front-of-the-meter costs and behind-the-meter costs, the latter being largely fixed costs which can comprise 30-40% of the installation’s capital costs.

Regulation and compliance can be a minefield, with permitting costs increasing. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), federally mandated but regulated locally, means requirements differ between states, even municipalities. ADA revisions average two per project, warned Leonard, with new requirements emerging almost weekly.

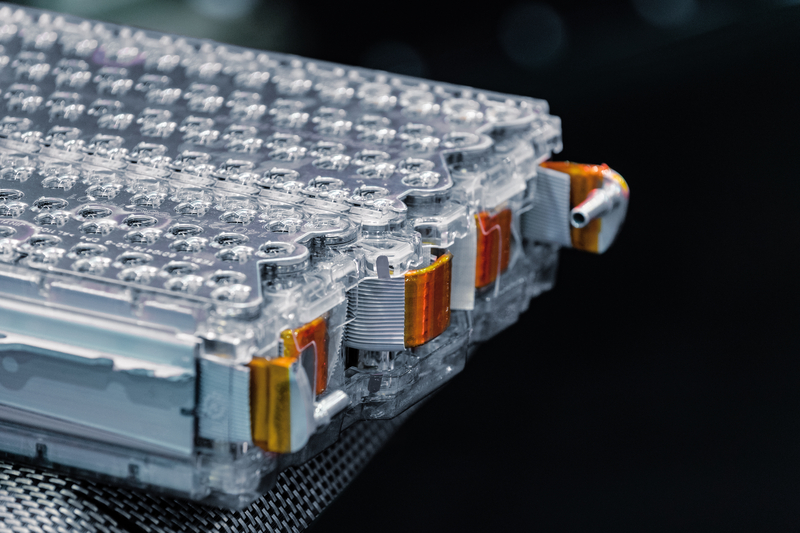

Current grid capacity is woefully insufficient according to Abramson. A six-bank of DCFCs uses the same energy as a high-rise office. One DCFC installed at a gas station consumes ten times the amount of power that fuel station is rated for. Providing the necessary power for future installations is a huge challenge.

Space at a typical interstate retail unit is often constrained, said Leonard. Installing even one DC charger can be difficult, let alone a battery backup system. Solar power is an option but not the total answer. Again, working creatively with local utilities will help, she stressed.

Abramson listed a number of ways to mitigate cost drivers and failure points such as locating EVSEs as close to power sources as possible, using networked chargers with built-in EMS for managed charging and using directional boring (not trenching) when possible. Both Abramson and Leonard place significant value on creating a single communication point for the entire supply chain. Future-proofing and maximising local expertise pay long-term dividends.