The USPS in December announced that by 2028 it would acquire 60,000 vehicles, including at least 45,000 that will be electrically powered. The conversion will ramp up with 100% of the USPS vehicles delivered from 2026 through 2028 expected to be electric.

THE GOOD NEWS

Adding such a high volume of electric vehicles is a key step in adoption, said Tim Johnson, professor of Energy and the Environment at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University.

The fact that the USPS is leading the way is particularly encouraging. “The service had resisted,” he said. “A year ago officials announced they were going with standard gasoline vehicles.”

Graphic: GreatBusinessSchools

Pushback from the Biden administration, among others, led the Postal Service to reevaluate.

“The numbers just for fleet turnover are staggering,” Johnson said. The Postal Service's substantial commitment to battery powered delivery vehicles is the latest in a series of pledges from national and state governments – not to mention consumers.

A great fit. “The USPS mail van is a prime candidate for electrification,” said Dan Bowermaster, senior program manager of Electric Transportation at EPRI – an independent, non-profit energy R&D institute.

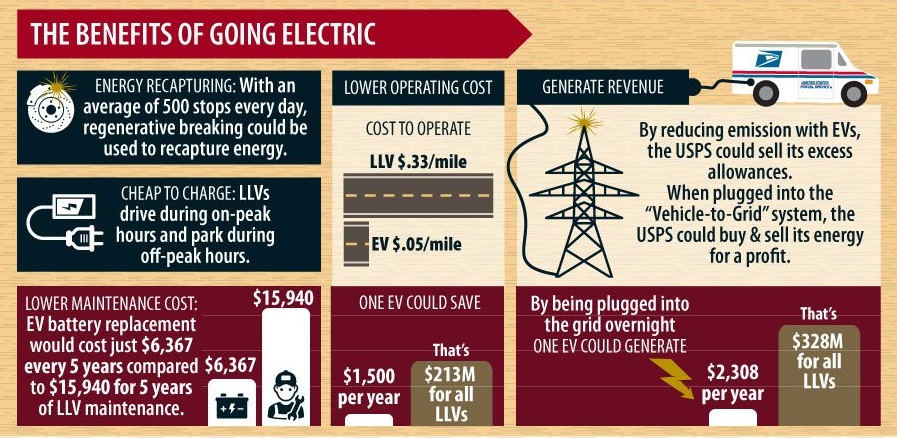

“It drives 21 miles a day at an average speed of 14mph, and stops 500 times,” he said, citing a study by Great Business Schools. “The average low speeds, short mileage, and lots of stops match extremely well with vehicle electrification.”

The USPS itself concluded that it could electrify 99% of its routes. Some are questioning why the service isn’t buying more EVs, Bowermaster said.

An article in The Atlantic pointed out several other advantages that the USPS can leverage with the transition to EVs. At day’s end, the vehicles return to the same centralised depots, which offer ideal spots to install charging facilities. In addition, the vehicles could recharge at night, when utility rates are lower.

“This is the absolute perfect fleet for electrification,” Patricio Portillo, a senior advocate in the climate-and-clean-energy program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, told the Atlantic.

The infrastructure is strong. The electric foundation is in place. Johnson doesn’t believe installing charging stations will be a big issue.

“Look back 100 years ago, when gasoline took off,” Johnson recalled. “We used to have just a few pumps. We added 100,000 gas stations in a decade.” That required installing pumps, building stations and transporting gasoline for hundreds of miles.

Bowermaster believes existing infrastructure is capable of handling an electrically powered postal fleet.

“Even at a conservative efficiency assumption of 3 miles per kilowatt hour, this means a mail van on average only needs about 7 kilowatt hours per night of recharge to complete its daily route,” he said.

“Since mail vans sit parked overnight for 8 to 10 hours, even low power Level 1 charging (120V outlet, 1.2 kW) would work. Again, to be conservative, low power Level 2 workplace charging would more than suffice for many USPS fleets.”

Others feel an obligation to convert. The Postal Service’s efforts will encourage others to follow suit, John Podesta, White House Senior Adviser for clean energy innovation, told the Washington Post.

Companies like Amazon, UPS and FedEx have announced plans for carbon neutrality. Podesta believes those efforts should accelerate due to the USPS announcement.

“I think it puts pressure on them to up their game, too,” Podesta remarked in the Post. “If the Postal Service can move out with this kind of aggressive plan, the public expects these companies that have made long-term announcements to catch up in the near term.”

CHALLENGES

Of course, obstacles will arise as the plan becomes a reality. “It will be interesting to see how the Postal Service manages charging,” Johnson said.

A big concern for Johnson is whether the current transformers and substations have the capacity to handle the load. “This isn’t about installing EV chargers,” he said. “Supplying the power is the issue. In many cases, there may need to be upgrades to the local distribution network.”

The smaller USPS branches will not be a problem. “For a small motor pool, the charging infrastructure is not a big deal,” Johnson said. “The power load wouldn’t be a constraint, and you can charge overnight when the grid has spare capacity and electricity rates are lower.”

Postal branches tend to be located in neighborhoods, where the electric power distribution network may be limited. Troubles could arise when a large number of delivery vehicles are consuming power at a particular location.

The higher volume would require faster chargers – which in turn would necessitate more robust distribution networks. “Efforts will need to be made to not overtax the system,” Johnson said.

Limiting the discussion to the USPS, Bowermaster doesn’t foresee the power system becoming overburdened. “Even a post office with a large fleet of mail vans will have the benefit of load diversity,” he said. “Some vans will need more kilowatt hours, some less, as each route is different. There is technology today that allows for power sharing, load management, etc.”

From a utility perspective, an electrified USPS is easily served, he said. “This is roughly the size of a large convenience store with AC and freezers.”

On balance, it’s not a close call: Converting the USPS is a great move, both Johnson and Bowermaster said.

“Many postal agencies around the world are already electrifying,” Bowermaster said. “As EPRI and industry studies have shown, justifications against electrifying transportation in the U.S. have not held up when scrutinized.”